History

Perhaps Britain’s best-known lighthouse, the Eddystone Lighthouse is only the latest of four lighthouses to have been built since 1698 on a very small, very dangerous rock 8.4 miles south of the NCI lookout at Rame Head.

Winstanley’s Tower 1698 – 1703

The first attempt to render the Eddystone safe to shipping was by an eccentric named Henry Winstanley.

As a showman he had established "Winstanley's Waterworks" near Hyde Park one of London's foremost popular attractions. In 1696 he commenced work on a steel structure and finding conditions considerably harder than he had envisaged doubtless began to wonder what he had let himself in for.

England was at war with France at this time and such was the importance of the Eddystone project that the Admiralty provided Winstanley with a warship for protection.

In 1697 a most unusual incident occurred – one morning at the end of June the ship did not arrive but instead a French privateer which carried Winstanley off to France. However when Louis XIV heard of the incident he ordered that Winstanley be immediately released, saying that "France is at war with England not with humanity". The importance of the Eddystone was now international.

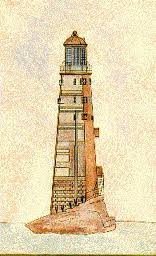

Rudyerd’s Tower 1709 – 1755

The next man to get a patent charter for the Eddystone was Captain Lovett who acquired the lease of the rock for 99 years.

By an Act of Parliament he was allowed to charge all passing ships a toll of 1d per ton, both inward and outward.His designer was a man named John Rudyerd, who was a silk mercer on Ludgate Hill; the trade of scientist or engineer did not really exist then and problems relating to those fields were approached by people as hobbies rather than professions. It seems remarkable that a person with no experience or proven knowledge of the subject should be selected to undertake such a difficult and dangerous task.

Taking a shipbuilder's rather than a house builder's approach he came up with a design based on a cone instead of Winstanley's octagonal shape. His final wooden tower, lit in 1709, proved much more serviceable and at last it seemed the problem had been solved – a lighthouse had been permanently established at the Eddystone built by one of the greatest amateurs.

The lighthouse stood for 47 years till the night of 2 December 1755 when the top of the lantern caught fire, probably through a spark from one of the candles. Henry Hall, the keeper on watch, who was 94 years old but said to be `of good constitution and active for his years', did his best to put out the fire by throwing water upwards from a bucket. While doing so, the leaden roof melted, and as his mouth was open whilst looking up, some of the molten lead ran down his throat. He and the other keeper battled continuously against the fire but they could do nothing as the fire was above them all the time - as it burnt downwards it gradually drove them out onto the rock.

The fire was observed from the shore by a Mr. Edwards, `a man of some fortune and more humanity'. The contemporary account says he sent off a boat which arrived at the lighthouse at 10 am after the fire had been burning for 8 hours. The sea was too rough for the boat to approach the rock so they threw ropes and dragged the keepers through the waves to the boat. The lighthouse continued to burn for five days and was completely destroyed.

Henry Hall lived for 12 days after the incident, and a Doctor Spry of Plymouth who attended him made a postmortem and found a flat oval piece of lead in his stomach which weighted over 7ozs. Dr. Spry wrote an account of this case to the Royal Society, but the Fellows were sceptical as to whether a man could live in this condition for 12 days. This so incensed him that, for the sake of his reputation, he performed many experiments on dogs and fowls pouring molten lead down their throats to prove that they could live!

Smeaton’s Tower 1759 – 1882

After experiencing the benefit of a light for 52 years, mariners were anxious to have it replaced as soon as possible. Trinity House placed a light vessel to guard the position until a permanent light could be built.

In 1756 a Yorkshireman, John Smeaton, who had been recommended by the Royal Society, travelled to Plymouth on an assignment which was to capture the imagination of the world. He had decided to construct a tower based on the shape of an English Oak tree for strength but made of stone rather than wood. For such a task he needed the toughest labourers, and many of the men employed had been Cornish Tin Miners. Press ganging had become a problem amongst the workforce, so to ensure that the men would be exempt from Naval Service, Trinity House arranged with the Admiralty at Plymouth to have a medal struck for each labourer to prove that they were working on the lighthouse.

Local granite was used for the foundations and facing, and Smeaton invented a quick drying cement, essential in the wet conditions on the rock, the formula for which is still used today. An ingenious method of securing each block of stone to its neighbour, using dovetail joints and marble dowels was employed, together with a device for lifting large blocks of stone from ships at sea to considerable heights which has never been improved upon.

Using all these innovations, Smeaton's tower was completed and lit by 24 candles on 16 October 1759. In the 1870's cracks appeared in the rock upon which Smeaton's lighthouse had stood for 120 years, so the top half of the tower was dismantled and re-erected on Plymouth Hoe as a monument to the builder. The remaining stump still stands on the Eddystone Rock.

Douglass’ Tower - 1882 Onwards

No time was lost in building another lighthouse on the rocks, and the task of building a new tower gave ample opportunity to incorporate many of the latest ideas in lighthouse construction, which by 1877 had become a much more refined business, largely due to the efforts of Robert Stevenson, who developed Smeaton's idea and contributed many of his own. Douglass used larger stones, dovetailed not only to each other on all sides but also to the courses above and below, and in 1882 the present Eddystone Lighthouse was completed and opened by the Duke of Edinburgh, who laid the final stone of the tower. At the same time, Smeaton's Tower was returned to the mainland and re-erected on Plymouth Hoe, where it still stands today.

The Eddystone was the first Trinity House rock lighthouse to be converted to automatic operation. To enable the work to be carried out a helipad was built above the lantern. The automation was completed and the light reintroduced on 18 May 1982, 100 years to the day since the opening of Douglass' tower.